KINGDOM OF REEDS: THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE OF SOUTHERN IRAQI MARSHES

Abdulameer al-Hamdani

Archaeologist - Iraq Heritage Senior Fellow

11th May 2015

Iraq Heritage Report

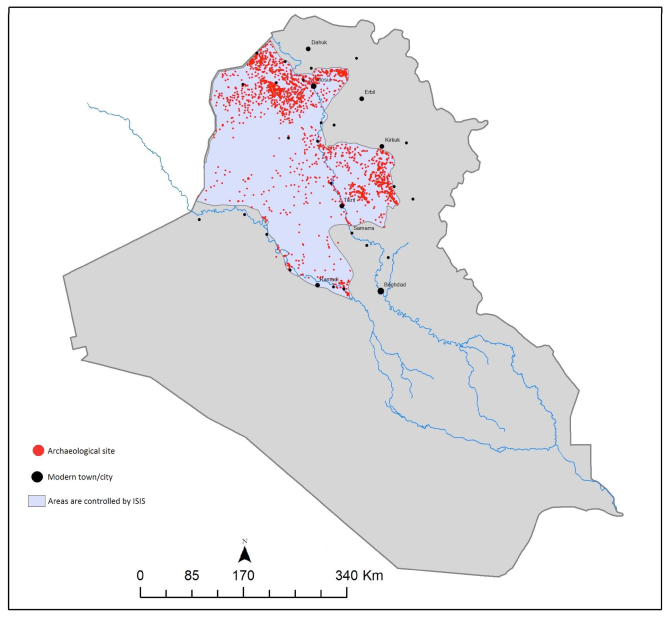

Although most of the Mesopotamian alluvial plain has been surveyed and documented, many areas remain without documentation. Among these areas are the southern marshes, which are located between and alongside the lower courses of the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers. The existence of the marshes when Robert Adams and his colleagues conducted their surveys in the 1960s meant that they were unable to connect the settlement patterns that they had observed with the gulf to the south. In 2003, I was able to initiate a series of surveys in southern Iraq, including areas that had been marshes before Saddam Hussein drained them in 1992. There are three main areas of marshes that we were able to explore: Howr al- Ḥammār, which is located east of Ur; the Central Marshes, which extend between the lower courses of the Tigris and the Euphrates; and Howr al-Ḥūwaiza, which starts from the Tigris eastward to the Iranian territories.

The objective of this survey was primarily to determine the nature of the ancient occupation and the settlement system in areas closer to the gulf than had been possible when the earlier surveys were carried out. However, this survey also gave us the opportunity to understand how rivers that were known from earlier surveys connect to the gulf. Before our survey, the only record of sites in this area was that by George Roux, who visited a handful of sites located at the southern edge of Howr al-Ḥammār in 1953, describing them as primarily Islamic and pre-Islamic in date1.

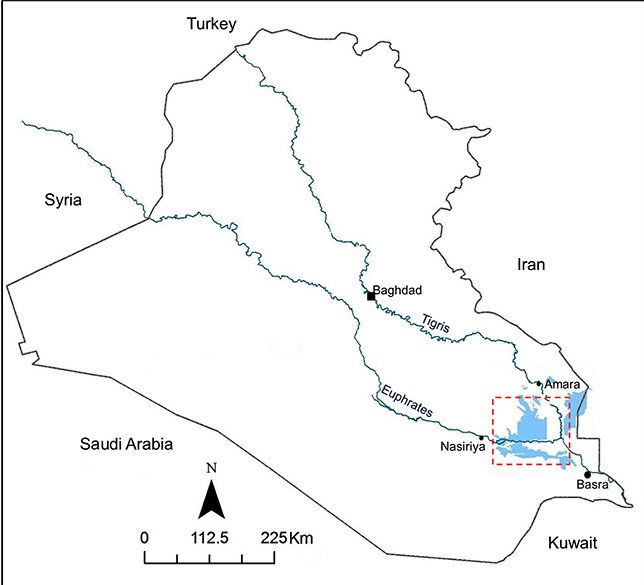

The survey was conducted periodically from 2003–2009, and was designed to record the sites before they were inundated. Colleagues from the southern provinces of Dhiqār, Maysān, and al- Baṣra contributed to this survey. Trucks were used on dry land and boats for water-covered areas, but in shallow or muddy marshes, walking was preferred even for considerable distances. Since 2008, a remote sensing technique was used to analyze the Digital Globe Quick Bird satellite images for part of the marshes in order to observe the landscape, and to trace courses of the ancient canal system. Also, the Geographic Information System (GIS) was used to map sites and features. Technical support was provided by Elizabeth Stone of State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Howr al-ḤammārIn Howr al-Ḥammār, most of the sites were located alongside the very clear traces of an ancient river. This was an extension to the south of the watercourse that passed to the east of the ancient city of Eridu and past Tell el-Leḥem1. This river ran west of Uruk downward toward Telūl al-Deḥaila and Umm al-Jamajim, which both date back to early second millennium BCE. At Eridu, the course turns east toward Telūl al-Ṣūlibiyāt, an Old Babylonian settlement (1763–1595 BCE), and then goes all the way to Tell el-Leḥem where it joins a canal that comes from Ur to form one course and runs eastward. Within our survey area, we traced it eastward until it disappeared north of the Basra oil field. As was the case with most of the sites surveyed by Henry Wright in the northern extensions of the ancient canal, most of the sites along its southern extensions dated back to the second and first millennia BCE.

Early second millennium sites are located at the western part of Howr al-Ḥammar, alongside the river when it passed Tell el-Leḥem. The ancient course of the river is very obvious in this area, and its two-meter depth is distinguishable from the surrounding flat plain. The local population called it Kary Seẹda. Significant sites include Oasir Thāmir and Abu Thahab. Oasir Thāmir is located 13 km east of Tell el- Leḥem, is almost 30 hectares in size, and consists of two mounds. On the larger, southern mound, we found the foundations of an Old Babylonian public building. Abu Thahab, a 30-hectare site, is located 30 km east of Tell el-Leḥem; it, too, has an important Old Babylonian public building.

These sites were occupied for a short time during the first dynasty of Babylon until the 11th year of the reign of the son of Hammurabi, Samsu-Iluna, the king of Babylonia (1750–1710 BCE), where he attacked the southern cities. As a reaction to this attack, the people of the south started rebelling against Babylon and created their own governmental structure, the socalled first Sealand Dynasty (ca. 1739–1340 BCE), which led to the collapse of the first Babylonian dynasty in the south. During this time, the canals and rivers shifted their beds and created marshes and swamps in lower southern Mesopotamia. Based on the site surface pottery, most of the second millenium sites in this area and northward up to Larsa have settlement that dates back to the first Sealand dynasty, which lasted from the late Old Babylonian through the early Kassite periods.

1 Georges Roux 1960. Recently Discovered Ancient Sites in the Hammar Lake District (Southern Iraq). Sumer 16/1–2:22-30.

2 Henry T. Wright 1981. The Southern Margins of Sumer, in Heartland of Cities, ed. Robert McC. Adams. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. Pp. 295– 346.

Kassite sites (1595–1155 BCE) were also represented in this area at the middle part of the ancient river. The most prominent site, Tell Abu Rūbāb, is located 38 km east of Tell el-Leḥem, is 75 ha, and is divided into two mounds by the ancient river. Tell Chirbāsy is the last Kassite site toward the eastern part of the ancient river, and is located 56 km east of Tell el-Leḥem. The Neo-Babylonian sites (626–539 BCE) are located close to the eastern end of the ancient river. The two most important sites were located at different ends of a rectangular island located at the eastern end of the watercourse — probably close to where it debouched into the gulf. Tell Abu Shuạib (25 ha) is located 69 km east of Tell el-Leḥem, and consists of four mounds, some of which post-date the main Neo-Babylonian occupation. Tell Abu Ṣalābīkh (44 ha) lies 2 km to the south of Tell Abu Shuảib, but is larger and higher. In 1952, George Roux found a shoulder of a pot inscribed with a cuneiform phrase that says “SHA.BIT-IA-KIN”. Bit-Yakin was the most powerful of the Chaldean tribes in the seventh century BCE, dominating the land around Ur.1

Figure 6.1. A map of Iraq showing the marshes. The dotted box shows the surveyed area. (Photo credit: Abdulameer al-Hamdani, 2014)

3Roux, ibid, p.27.

-4.png)

Figure 6.2. The map shows archaeological sites and ancient canals in the southern Iraqi marshes. (Photo credit: Abdulameer al-Hamdani, 2014)

The Sassanian (224–651 AD) and Islamic settlements, mostly Abbasid (750–1258 AD), are located at the eastern edge of Howr al-Ḥammar next to Shaṭ al-Ạrab. Among them are Tell Ḥareer, Tell Nahr Ūmer, Tell al-Nukhaila, and Telūl al-Deir. At the northern side of Howr al-Ḥammar below the Euphrates, a group of late Islamic sites are located alongside a bed of an extinct canal called Shaṭ al-Ḥamīdī. Among them are Eshān Umm al-Wadiẹ, al-Midag, al-Telail, and al-Khaiṭ. At the eastern end of Shaṭ al- Ḥamīdī at al-Chibāyesh, another group of small late Islamic sites is located that includes al-Ritba, Muạibid al-Dibin, and Abū al-Sibūs. Another line of Islamic settlements is located at the southern side of Howr al-Ḥammar that sharply abuts the western desert. Among these is Tell al-Ḥaṣbi, which is located 70 km east of Tell el-Leḥem and 5 km south of Tell Abu Shuạib. The surface of the 122 ha site is covered by Abbasid glazed pottery; traces of wall foundations are visible on the western part of the settlement

My team and I were able to identify sixty sites, thirty sites dating to the Isin- Larsa, Old Babylonian, Kassite, and Neo-Babylonian periods, and thirty sites dating to the late Sassanian, and Abbasid period and beyond. Some of the sites are large enough to be towns and even cities, but the majority are villages and hamlets.

The Central Marshes and Howr al-ḤūwaizaAs plans developed to re-flood the Central Marshes in 2007, I conducted a survey of the Central Marshes starting with an area that was going to be re-flooded soon, and then I extended my work to include most of these marshes.

Shahrabān is located about 30 km south of Wasiṭ. The oval shape of the 24 ha settlement was surrounded by a wall, the bricks of which are scattered all over the site, as well as sherds of glazed pottery and fragments of glass dated to the Sassanian and Abbasid periods. At 20 km south of Shahrabān is the 20 ha circular site of Fārūth. The site has a small Sassanian settlement and was reoccupied in the Abbasid period. It is situated at a nexus between what was once a series of watercourses. Raṣāfat Wāsiṭ, which means the harbor of Wāsiṭ, is located 16 km southwest of Farooth, and alongside the ancient river, Shaṭ al-Akhaḍer, that divided the site into two mounds. The western mound, the largest and highest one (24 ha), has a density of architectural traces and foundations. The surface is covered by typical Abbasid glazed pottery and glass, with indications of a small Sassanian occupation. The eastern mound (8.4 ha) appears to be a harbor where a density of pithos and bitumen is scattered alongside its western edge. Telūl al-Qaṭṭārāt is located 17 km south of Fārūth. It consists of seven mounds scattered in an area of 3 square km. In one of the mounds, al-Qaṭṭār al-Janūbī, there is the shrine of Aḥmed al-Rifāẹī (1118–1182 AD), who was the founder of the Rifāẹī Sūfī. Telūl al-Jāmida is located 104 km south of Wāsiṭ and 17 km southeast of the ancient city of Nina, and situated alongside the lower course of the ancient river. The surface of the 32 ha settlement is covered with sherds of glazed pottery dated to the third and fourth Islamic centuries. Baked bricks are also scattered, specifically at the southern part of the settlement, where traces of walls are visible on the surface as well as remains of a baked-brick arch.

1. Bāṭiḥat Wāsiṭ: The upper part of the Central Marshes and Jeziret Seid Aḥmed al-RifāẹīThis region is located south of the Islamic city of Wāsiṭ and goes down to the east of the ancient cities of Girsu and Lagash. There was a well-organized and large-scale Sassanian irrigation system of canals and dams. This system collapsed dramatically at the end of the Sassanian period, specifically in the year 627 AD, when the Sassanians were engrossed in repelling the Islamic conquest’s armies1. The effect of this collapse turned the land into marshes until the Umayyad and early Abbasid periods, when the state trended towards reviving land by re-digging the Sassanian canals, digging new canals, and maintaining dams and river levees. The satellite imagery and ground survey in this area provide a clear picture to follow the courses of an ancient major river from Wāsiṭ downward to the current lower arm of the Tigris before its confluence with the Euphrates. The local population calls the dried course of this river Shaṭ al-Akheḍer. The most important selected archaeological sites in this area are Shahrabān, Fārūth, Telūl al-Raṣāfa, Telūl al-Qaṭṭārāt, Telūl Khamīs, and Tell al-Jāmida.

Shahrabān is located about 30 km south of Wasiṭ. The oval shape of the 24 ha settlement was surrounded by a wall, the bricks of which are scattered all over the site, as well as sherds of glazed pottery and fragments of glass dated to the Sassanian and Abbasid periods. At 20 km south of Shahrabān is the 20 ha circular site of Fārūth. The site has a small Sassanian settlement and was reoccupied in the Abbasid period. It is situated at a nexus between what was once a series of watercourses. Raṣāfat Wāsiṭ, which means the harbor of Wāsiṭ, is located 16 km southwest of Farooth, and alongside the ancient river, Shaṭ al-Akhaḍer, that divided the site into two mounds. The western mound, the largest and highest one (24 ha), has a density of architectural traces and foundations. The surface is covered by typical Abbasid glazed pottery and glass, with indications of a small Sassanian occupation. The eastern mound (8.4 ha) appears to be a harbor where a density of pithos and bitumen is scattered alongside its western edge. Telūl al-Qaṭṭārāt is located 17 km south of Fārūth. It consists of seven mounds scattered in an area of 3 square km. In one of the mounds, al-Qaṭṭār al-Janūbī, there is the shrine of Aḥmed al-Rifāẹī (1118–1182 AD), who was the founder of the Rifāẹī Sūfī. Telūl al-Jāmida is located 104 km south of Wāsiṭ and 17 km southeast of the ancient city of Nina, and situated alongside the lower course of the ancient river. The surface of the 32 ha settlement is covered with sherds of glazed pottery dated to the third and fourth Islamic centuries. Baked bricks are also scattered, specifically at the southern part of the settlement, where traces of walls are visible on the surface as well as remains of a baked-brick arch.

The 126 sites of this area are basically late Sassanian settlements that were abandoned in the early Islamic period, but were partially reoccupied during the Umayyad period and largely during the Abbasid period, specifically during the Emirate of al- Beṭāieḥ. The emirate was established by Imran bin Shahin in al- Beṭāieḥ, the great marshes of southern Iraq, in the mid-tenth century AD and remained in power from 949– 1021 AD. Indications of a small Parthian occupation (247 BCE– 224 AD), and post-Abbasid occupations, particularly the Ilkhanate period (ca. 1258– 1335 AD), exist. The sites can be classified as three cities, twelve towns, and forty-five villages; the rest are small villages and hamlets.

2. Bāṭiḥat of Maysān: The Central Marshes and Howr al-ḤūwaizaMaysān was a state founded by Hyspaosines during the first century BCE in lower Mesopotamia, and called Mesene by Starbo, and Charācene by Pliny. It was called Shādh Bāhman in the Sassanian times, but its Aramaic form of Maysān was later adopted by the Arab conquerors and so survived as the name of southern Iraq until the late Middle Ages1. Today the Central Marshes and Howr al-Ḥūwaiza are the territories of Maysān. The 110 sites in this area were Sassanian settlements reoccupied in the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, specifically during the Emirate of al- Beṭāieḥ in the mid-tenth century AD. A considerable number of settlements were established in the Seleucid period through the Parthian period, which is the time of the state of Masyān (Characene/ Mesene) (ca. 140 BCE–220 AD). A number of sites were the former homes of the Mandaean sect since many objects such as Mandaic lead rolls and scribed gold and silver amulets have been found in sites. The most important selected archaeological sites in this area are Tell al-Maḍār, Tell Madina, Tell al-Ạqor, Tell Aṣlān, and Telūl al-Mūsaiḥib.

Al-Maḍār was a city of much importance at the time of the Arab conquest, being the capital of the Dasty-Maysān region1. The 42 ha site of al-Maḍār is located 20 km southeast of Qalāt Ṣalih on the east bank of the Tigris. The shrine of Ạbdullah Bin Ạli is situated on top of the site. Tell Madina is located 25 km south of al-Maḍār, north of the Tigris–Euphrates confluence. The surface of the 40 ha settlement is mostly covered by pottery of the third and fourth Islamic centuries, whereas typical Sassanian pottery covers the eastern part of the settlement. Tell al- Ạqor is located 32 km southwest of al-Maḍār, on an island of 87 ha in the Central Marshes, alongside the north branch of Shaṭ al-Kheḍer, west of the Tigris. The distribution of the pottery indicates a large Abbasid occupation upon a late Sassanian settlement. An elderly man from a nearby village told me that people used to collect lead from the surface of the site to make cartridges for hunting birds; these are the so called Mandaic scribed lead rolls.

4 Al-Balāthiry 1901. Fitūḥ al-Būldān. Cairo, p.358.

5 J. Hansman 1970. Urban Settlements and Water Utilization in South-western Khuzistan and South-eastern Iraq from Alexander the Great to the Mongol Conquest of 1258. University of London, London, p. 67.

6 Yāqūt al-Ḥamawi 1977. Mu’jam al-Būldān IV. Dār Ṣād, Beirut, p. 468.

Tell Aṣlān is located 50 km southwest of al-Maḍār, 5 km north of the Euphrates, and is situated alongside the southern branch of Shaṭ al-Kheḍer. The site consists of small and large mounds. The 20 ha mound was occupied in the Sassanian period. The 50 ha mound is covered with Abbasid glazed pottery, which marks a large Abbasid occupation. Telūl al- Mūsaiḥib is located 30 km southeast of Telūl al-Jāmida, alongside the southern branch of Shaṭ al-Akheḍer. It contains four mounds that extend for an area of 200 ha. The 80 ha mound is covered with baked bricks and typical Sassanian pottery, which could mark the location of a public building. The 50 ha eastern mound is covered by typical Abbasid glazed pottery, while the southern 28 ha mound has a density of kiln remains such as triple-spacers, and molds for making slipper-shaped coffins, which indicate an industrial district.

3. Karkh Maysān: Howr Majnūn and the area east of Shaṭ al-ẠrabThe eastern side of Shaṭ al-Arab consists of a high level threshold that precludes inundation, as it is located between the shallow basin of the sedimentation where the Euphrates and Tigris pour their waters into extensive marshes, and the delta slopes downward towards the gulf in the south1.

On this threshold, many sites are distributed between al-Qūrna in the north and al-Baṣra in the south, alongside the ancient course of Shaṭ al-Ạrab (Dijla-al- Ạwra). Other sites are located alongside the ancient course of Karkha River (an ancient Eulaeus canal), which rises in Iran and flows into the Ḥuwaiza marsh in Iraq1. The fourteen sites were occupied in the Seleucid period and its succeeding Parthian period as a part of the semi-independent kingdom of Characene/ Mesene, in the Sassanian period as a part of Bahman Ardeshīr district, and in the Islamic periods as a part of the Kuwar Dijla region. Today, the lower parts of Howr al-Ḥūwaiza and Howr Majnūn from Shaṭ al-Ạrab eastward to Khuzstān are the territories of Karkh Maysān. The two important sites are Telūl Khiāber and Telūl al-Meglūba. Telūl Khiāber (ancient Karkh Maysan), a 336 ha walled site, is located 58 km northeast of old Baṣra, and 4 km east of the current course of Shaṭ al-Ạrab. It consists of seven mounds of different sizes. Telūl al-Meglūba (ancient Furāt Maysān), 230 ha, is located 16.4 km southeast of Telūl Khiāber. The two sites were ports that played a major role in the trade between the gulf and Mesopotamia, and further Syria and the eastern Mediterranean Sea1.

ConclusionThe surveys show that the marshes of southern Iraq were occupied at very different periods. We were able to document 304 sites, most of which were hitherto unknown.

The periodic distribution of the sites in Howr al-Ḥammār, from the second and first millennia BCE to the first millennium AD, could indicate the progressive movement of the coast of a body of water. It could be a tremendous marsh, similar to the Howr al- Ḥammār, linking the lower Mesopotamian to the gulf. Sites of the second and first millennia BCE were located alongside an ancient canal that started from Tell el-Lehem and ran eastward to Shaṭ al-Ạrab, where it disappeared north of the Basra oil fields. These sites have small-scale occupation from Isin-Larsa through Old Babylonian periods, but they flourished during the first Sealand dynasty through the Kassite period, but did gradually decline during the post-Kassite period. The late Islamic sites were located alongside a canal that ran south of the present course of the Euphrates. The eastern side of Shaṭ al- Ạrab was occupied in the Seleucid period through the Parthian period, and flourished during the late Sassanian period through the Umayyad and Abbasid periods.

There is no indication of occupation earlier than Parthian in the area east and south of the ancient cities of Girsu-Lagash-Nina on Shaṭ al-Gharrāf eastward to the Tigris. This area, the Central Marshes and Jeziret Seid Aḥmed al-Rifāẹī south of Wāsiṭ, was intensively occupied in the Sassanian period; settlements of this period were located alongside a large-scale irrigation canal system. Most of the sites were abandoned at the Islamic conquest, when the Sassanian canal system collapsed and the lands turned to marshes. This system was restored partially in the Umayyad period when some of the flooded lands had been dried and reclaimed. The settlements grew in size and number, and the canal system was largely restored during the Abbasid period. However, this system collapsed partially in the tenth century AD when the Buyid dynasty controlled Iraq, but it was restored in the thirteenth century, when towns and villages flourished and agricultural fields were productive. In the Ottoman period, the area turned into a desert and settlements and canals were abandoned forever. The marshes moved back east and south to the lower course of the Tigris.

AcknowledgementsThis work could not be done without the hard work of my team members: Wasan A. Isā, Ạāmer A. Ạṭiyya, Abāther R. Sạdūn, Wiṣāl N. Jāsim, and Yaḥyā G. Ạlwān. I am grateful to my colleagues: Ạdnān H. Hesūny and Mūrtaḍā H. Jaẹfar of Maysān province, and Qahṭān Al Abeed of al-Baṣra province, for sharing some data. I want to thank Dr. Ạzzām Ạlwash and Eng. Jāsim Al-Asadi of the Iraq-Nature Organization who provided the opportunity for me to survey the Central Marshes in 2007. I would like to thank the local guides, Ạli Hraija Sūltān, Mūnāf Fahad al-Khayyūn, Khashin Ḍẹain, and Abu Fātma al-Bazzūni. Many thanks to Dr. Elizabeth Stone of SUNY at Stony Brook for the useful comments and suggestions, and for providing valuable satellite images.

7 Roux ibid, p.22

8 Hansman, ibid, p.183.

9 Hansman, ibid, p.188.

THE OXFORD POSTGRADUATE CONFERENCE IN ASSYRIOLOGY

By George Richards

Archaeologist - Iraq Heritage Senior Fellow

29th April 2015

Iraq Heritage Report

In an address that declared the Oxford Postgraduate Conference in Assyriology 2015 open, Dr Jacob Dahl, Associate Professor of Assyriology at the University of Oxford, gave a poignant reminder of the critical importance of this field of study following recent acts of cultural heritage destruction in Iraq and Syria by the Islamic State organisation: “The best way to preserve the history of Mesopotamia is through the digitisation of source material here [in Oxford and other academic institutions] and, as we have seen in recent weeks, in the countries of origin.”

The conference, held on 24-25 April 2015 at Wolfson College, Oxford, covered a wide range of fields of Assyriological study, from close textual and linguistic analysis, to the art, architecture and history of ancient Mesopotamia. The annual conference is held as a forum in which postgraduate students from around the world can discuss working theories and present papers in a more relaxed setting to a doctoral viva. Attendees and speakers had come from as far afield as America and Japan, as well as from traditional centres of Assyriological study in Germany and France.

Attendees of the Oxford Postgraduate Conference in Assyriology 2015

A common thread among the lectures was the breadth of the field of Assyriology still to be to explored. Dr Dahl, in his address, recounted the surprisingly short history of Assyriology at Oxford: a readership was only established at the turn of the twentieth century, compared to the creation of the Laudian chair in Arabic in the seventeenth century, and the Regius chair in Hebrew in 1546. In delivering their papers, many of the students identified gaping holes in the field: the translation of repeated idiomatic expressions and common regnal styles; the practical use of tablets inscribed with text; or the origins and extent of Sumerian culture.

The capacity for significant advances still to be made in the field of Assyriology emphasises the critical need to prevent the destruction of ancient Mesopotamian antiquities and archaeological sites in Iraq and Syria.

A clay tablet etched with the tangled wedges of the cuneiform script may well have been photographed, transliterated and even translated, but in a captivating lecture at this year’s conference Klaus Wagensonner, of the Universities of Vienna and of Oxford, demonstrated the importance of being able to re-photograph the clay fragments in new positions as a way of revealing the original shape and size of a tablet and, by extension, its possible function. New technological advances will also allow tablets to be subjected to novel analytical techniques, such as infra-red scans, or chemical analysis to determine the geographic origin of the clay. None of this will be possible for tablets that have been destroyed in museums or ancient sites, or stolen for sale on the black market where they are put beyond the reach of scholars.

The same is true for the study of the ruined palaces and cities and Nimrud and Nineveh, where the statuary has been smashed by Islamic State and the archaeological sites ravaged by looters burrowing small potholes in search of antiquities.

The precarious state of the archaeological record in Iraq and Syria, especially in the face of the threat from Islamic State, underscores the importance of the field of Assyriology. The new generation of Assyriologists unlocking the secrets of ancient Mesopotamia at the University of Oxford last week have their parts to play; but, as Dr Dahl noted, now is also the time for redoubling efforts to preserve and to study Mesopotamian heritage in the countries of origin.

George Richards, Senior Fellow at Iraq Heritage, attended the Oxford Postgraduate Conference in Assyriology 2015. The Conference was founded in 2012 and is organised with the support of the Oriental Institute at the University of Oxford, the British Institute for the Study of Iraq, the Lorne Thyssen Research Fund for Ancient World Topics, and Wolfson College.