The ancient city of Ashur is located on the Tigris River in northern Mesopotamia in a specific geo-ecological zone, at the borderline between rain-fed and irrigation agriculture. The city dates back to the 3rd millennium BC. From the 14th to the 9th centuries BC it was the first capital of the Assyrian Empire, a city-state and trading platform of international importance. It also served as the religious capital of the Assyrians, associated with the god Ashur. The city was destroyed by the Babylonians, but revived during the Parthian period in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

Statement of Significance

Criterion iii: Founded in the 3rd millennium BCE, the most important role of Ashur was from the 14th to 9th century BCE when it was the first capital of the Assyrian empire. Ashur was also the religious capital of Assyrians, and the place for crowning and burial of its kings. Criterion iv: The excavated remains of the public and residential buildings of Ashur provide an outstanding record of the evolution of building practice from the Sumerian and Akkadian period through the Assyrian empire, as well as including the short revival during the Parthian period.

Long Description

Founded in the 3rd millennium BC, the most important role of Ashur was from the 14th to 9th centuries BC when it was the first capital of the Assyrian empire. Ashur was also the Assyrian religious capital and the place for crowning and burial of its kings. The excavated remains of the public and residential buildings of Ashur provide an outstanding record of the evolution of building practice from the Sumerian and Akkadian period through the Assyrian empire, as well as including the short revival during the Parthian period.

The ancient city of Ashur (Assur, modern Qal'at Sherqat) is located 390km north of Baghdad. The settlement was founded on the western bank of the Tigris. The excavated remains consist of superimposed archaeological deposits, the earliest from the Sumerian Early Dynastic period (early 3rd millennium BC), then the Akkadian and Ur III periods, followed by the Old, Middle and Neo-Assyrian (ending mid-1st millennium BC) periods, and finally, the Hellenistic period and that of the Arab kings of Hatra.

Structurally, the city of Ashur was divided into two parts: the old city (Akkadian libbi-ali, the heart of the city), which is the northern and largest part of Ashur, and the new city (Akk. alu-ishshu), which was constructed around the mid-2nd millennium BC. The major features of the city now visible on-site consist of architectural remains: the ziggurat and the great temple of the god Ashur, the double temple of Anu and Adad, the temple of Ishtar, the Sumerian goddess of love and war, the Old Palace with its royal tombs and several living quarters in many parts of the city. The city was surrounded by a double wall with several gates and a big moat. The majority of the buildings of the city were built with sun-dried mud-bricks with foundations of quarried stones or dressed stone, depending on the period. Artistic objects and parts of architectural remains of the city are at present on display in the major museums of the world.

Historical Description

The history of the city of Ashur goes back to the Sumerian Early Dynastic period (first half of the 3rd millennium BCE). Some remains may even date to preceding periods. For this early part the stratigraphic excavation of the temple of Ishtar provided substantial information about the development of the religious architecture. Two of the five major building stages of it belong to this period. During the Akkadian empire (ca 2334-2154 BCE) Ashur was an important centre, and a governor of the third dynasty of Ur (2112-2004 BCE) ruled over the city which had to pay taxes to the central administration in the south. Still, the temple of Ishtar and its findings remain the main archaeological reference point. As an independent citystate Ashur became capital of Assyria and the Assyrians during the 2nd millennium BCE starting with the Old- Assyrian rulers Erishum, Ilushuma and Shamshi-Adad I and thereafter with the Middle-Assyrian kings Eriba- Adad I and Ashuniballit I. From here, the military campaigns of the Middle-Assyrian kings Tukulti-Ninurta I and Tiglathpileser I started and laid the foundation for the territorial expansion of the Assyrian empire to the west, ie Syro-Mesopotamia and the Levant, and other adjacent regions. For the 2nd millennium BCE a systematic building programme is attested for Ashur, culminating in the Middle-Assyrian period, when king Tukulti-Ninurta I not only renovated or reconstructed the majority of the temples (among them the temple of Ishtar), but terraced a large area for the his New Palace (the building was not erected since the king founded a new residential city named Kar-Tukulti- Ninurta, further upstream).

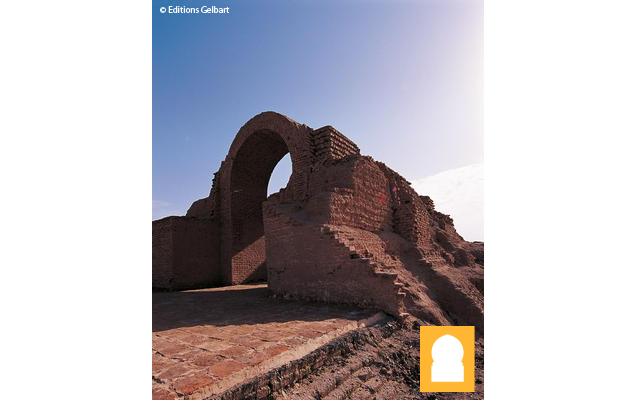

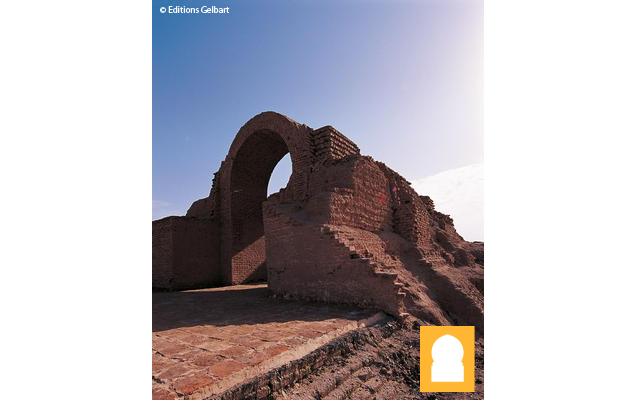

Ashur remained political capital until the reign of the Neo- Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE), who moved it to Kalhu (modern Nimrud). After that, Ashur continued to be an important religious and provincial Assyrian centre even though it had lost its function as national capital. The Neo-Assyrian kings executed restoration work at the main sanctuaries and palaces of Ashur as it was requested by the inscriptions of their predecessors and erected the royal burial place within the area of the Old royal palace. The majority of the private houses and living quarters date to this Neo-Assyrian period and provide important information about domestic architecture and the conditions of life of those parts of the Assyrian society not belonging to the royal elite. Special attention was received by the more than 1,000 inhumations in graves and tombs, mainly located inside the buildings, which provide important information on aspects of burial rites and funerary culture. The site survived the fall of the Assyrian empire in the 7th century BCE, and it flourished in the Hellenistic and Parthian periods until the 2nd century CE. The Parthian palace and a temple close to the ziggurat are architectural testimonies of this period. Presently, residential areas of the Parthian period are being excavated.

Source: Unesco

A large fortified city under the influence of the Parthian Empire and capital of the first Arab Kingdom, Hatra withstood invasions by the Romans in A.D. 116 and 198 thanks to its high, thick walls reinforced by towers. The remains of the city, especially the temples where Hellenistic and Roman architecture blend with Eastern decorative features, attest to the greatness of its civilization.

Long Description

Hatra is an excellent example of the fortified cities laid out on the circular plan of the eastern city, such as Ctesiphon, Firouzabad or Zingirli. The perfect condition of the double wall in an untouched environment sets it aside as an outstanding example of a series which covers the Parthian, Sassanid, and early Islamic civilization. It provides, moreover, exceptional testimony to an entire facet of Assyro-Babylonian civilization subjected to the influence of Greeks, Parthians, Romans and Arabs.

Although there are few texts referring to the obscure beginnings of Hatra, it seems that a smallish Assyrian settlement grew up in the 3rd century BC becoming a fortress and a trading centre. Founded by nomadic horsemen from a Khorasan tribe, the Parthian empire of the Arsacid dynasty (247 BC-AD 226) claimed to be the successor of the Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus. In the 2nd century BC, it flourished as a major staging-post on the famous oriental silk road to become another of the great Arab cities as Palmyra in Syria, Petra in Jordan, and Baalbek in Lebanon. This Eastern monarchy was a source of concern for the Romans who sought unsuccessfully to destroy it.

With this historical background, the site of Hatra, a large fortified city, the remains of which are to be seen in the middle of the desert 110km south-west of Mosul, can be taken as a symbol of the struggles which opposed Parthians and Romans for the spoils of the old empire of Alexander.

The city was seized unsuccessfully in 116 by Trajan (who died in Cilicia the following year); again it resisted Septimius Severus in 198 who, however, after having taken Ctesiphon and annexed Mesopotamia was acclaimed in Rome with the title of Parthicus Maximus. Some architecture and some inscriptions seem to point to a form of Roman occupation or of a Romano-Hatrene alliance in the AD 230s and inscriptions point to the rule of emperor Gordian III. Hatra could therefore be seen as the furthest extent of the empire at that time. Shortly thereafter Hatra was destroyed by Ardashir I (226-42), the founder of the Sassanid dynasty.

The present-day remains date back to between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD. The remains of the city, especially the temples where Hellenistic and Roman architecture blend with Eastern decorative features, attest to the greatness of its civilization. The fortifications were immense: the city's defences are comprised of two walls which separate a wide ditch. The external wall is an earthen bank; the inner wall is built from stone and has four fortified gates which roughly correspond to the four cardinal points. In the heart of this round city of almost 2 km in diameter, a rectangular temenos lies in an east-west direction. It is surrounded by a stone wall interrupted by towers. A north-south wall divides it into two unequal spaces. The function of this temenos - where there is a heavier concentration of temples in the west space - seems to have been both religious and commercial: shops looking on to a pilastered portico have been found on each of the four sides of the rectangle.

In the very centre of Hatra lies the temple complex dedicated to several Hatrene gods, the chief of which was the Sun god Shamash. Around 156, Hatra was governed by Arab rulers: prominent among them was Nasr, father of the first two kings of Hatra: Lajash and Sanatruq. The latter completed the Temple of Shamash, Sculptures have been discovered to Apollo (Balmarin in the Hatrene religion), Poseidon, Eros, Hermes, Tyche (the guardian goddess of Hatra) and Fortuna.

Source: Unesco

Samarra Archaeological City

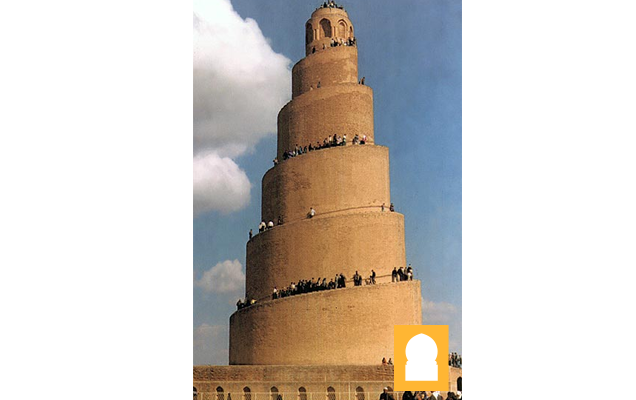

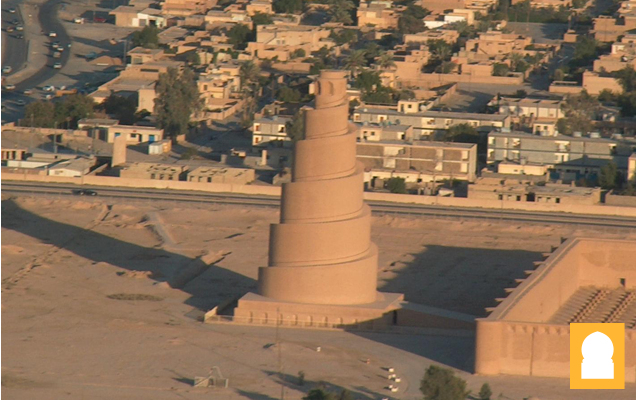

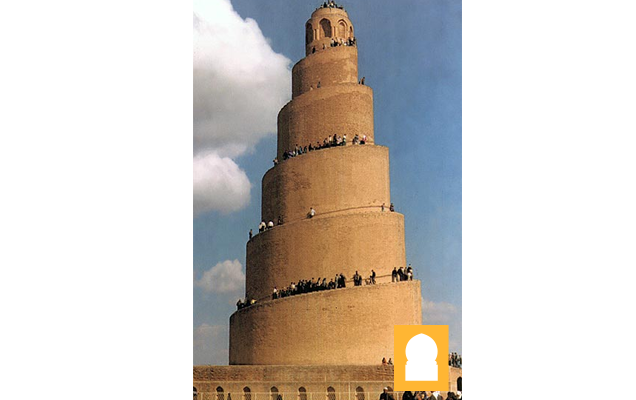

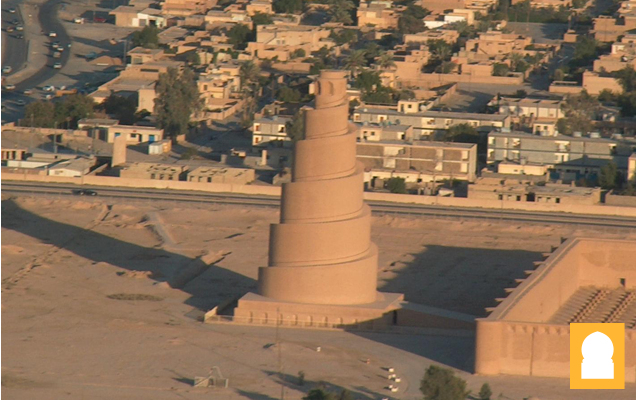

Samarra Archaeological City is the site of a powerful Islamic capital city that ruled over the provinces of the Abbasid Empire extending from Tunisia to Central Asia for a century. Located on both sides of the River Tigris 130 km north of Baghdad, the length of the site from north to south is 41.5 km; its width varying from 8 km to 4 km. It testifies to the architectural and artistic innovations that developed there and spread to the other regions of the Islamic world and beyond. The 9th-century Great Mosque and its spiral minaret are among the numerous remarkable architectural monuments of the site, 80% of which remain to be excavated.

Outstanding Universal Value

The ancient capital of Samarra dating from 836-892 provides outstanding evidence of the Abbasid Caliphate which was the major Islamic empire of the period, extending from Tunisia to Central Asia. It is the only surviving Islamic capital that retains its original plan, architecture and arts, such as mosaics and carvings. Samarra has the best preserved plan of an ancient large city, being abandoned relatively early and so avoiding the constant rebuilding of longer lasting cities.

Samarra was the second capital of the Abbasid Caliphate after Baghdad. Following the loss of the monuments of Baghdad, Samarra represents the only physical trace of the Caliphate at its height.

The city preserves two of the largest mosques (Al-Malwiya and Abu Dulaf) and the most unusual minarets, as well as the largest palaces in the Islamic world (the Caliphal Palace Qasr al-Khalifa, al-Ja'fari, al Ma'shuq, and others). Carved stucco known as the Samarra style was developed there and spread to other parts of the Islamic world at that time. A new type of ceramic known as Lustre Ware was also developed in Samarra, imitating utensils made of precious metals such as gold and silver.

Criterion (ii): Samarra represents a distinguished architectural stage in the Abbasid period by virtue of its mosques, its development, the planning of its streets and basins, its architectural decoration, and its ceramic industries.

Criterion (iii): Samarra is the finest preserved example of the architecture and city planning of the Abbasid Caliphate, extending from Tunisia to Central Asia, and one of the world's great powers of that period. The physical remains of this empire are usually poorly preserved since they are frequently built of unfired brick and reusable bricks.

Criterion (iv): The buildings of Samarra represent a new artistic concept in Islamic architecture in the Malwiya and Abu Dulaf mosques, in the form of a unique example in the planning, capacity and construction of Islamic mosques by comparison with those which preceded and succeeded it. In their large dimensions and unique minarets, these mosques demonstrate the pride and political and religious strength that correspond with the strength and pride of the empire at that time.

Since the war in Iraq commenced in 2003, this property has been occupied by multi-national forces that use it as a theatre for military operations.

The conditions of integrity and authenticity appear to have been met, to the extent evaluation is possible without a technical mission of assessment. After abandonment by the Caliphate, occupation continued in a few areas near the nucleus of the modern city but most of the remaining area was left untouched until the early 20th century. The archaeological site is partially preserved, with losses caused mainly by ploughing and cultivation, minor in comparison with other major sites. Restoration work has been in accordance with international standards.

The conditions of integrity and authenticity appear to have been met, to the extent evaluation is possible without a technical mission of assessment. After abandonment by the Caliphate, occupation continued in a few areas near the nucleus of the modern city but most of the remaining area was left untouched until the early 20th century. The archaeological site is partially preserved, with losses caused mainly by ploughing and cultivation, minor in comparison with other major sites. Restoration work has been in accordance with international standards.

The boundaries of the core and buffer zones appear to be both realistic and adequate. Prior to current hostilities, the State Party protected the site from intrusions, whether farming or urban, under the Archaeological Law. Protective procedures have been in abeyance since 2003 and the principal risk to the property arises from the inability of the responsible authorities to exercise control over the management and conservation of the site.

Source: Unesco

The conditions of integrity and authenticity appear to have been met, to the extent evaluation is possible without a technical mission of assessment. After abandonment by the Caliphate, occupation continued in a few areas near the nucleus of the modern city but most of the remaining area was left untouched until the early 20th century. The archaeological site is partially preserved, with losses caused mainly by ploughing and cultivation, minor in comparison with other major sites. Restoration work has been in accordance with international standards.

The conditions of integrity and authenticity appear to have been met, to the extent evaluation is possible without a technical mission of assessment. After abandonment by the Caliphate, occupation continued in a few areas near the nucleus of the modern city but most of the remaining area was left untouched until the early 20th century. The archaeological site is partially preserved, with losses caused mainly by ploughing and cultivation, minor in comparison with other major sites. Restoration work has been in accordance with international standards.