THe Cradle of Civilisation

Mesopotamia, the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (in modern day Iraq), is often referred to as the cradle of civilization because it is the first place where complex urban centers grew. The history of Mesopotamia, however, is inextricably tied to the greater region, which is comprised of the modern nations of Egypt, Iran, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, the Gulf states and Turkey. We often refer to this region as the Near or Middle East.

What's in a name?

Why is this region named this way? What is it in the middle of or near to? It is the proximity of these countries to the West (to Europe) that led this area to be termed "the near east." Ancient Near Eastern Art has long been part of the history of Western art, but history didn't have to be written this way. It is largely because of the West's interests in the Biblcial "Holy Land" that ancient Near Eastern materials have been be regarded as part of the Western canon of the history of art.

The land of the Bible

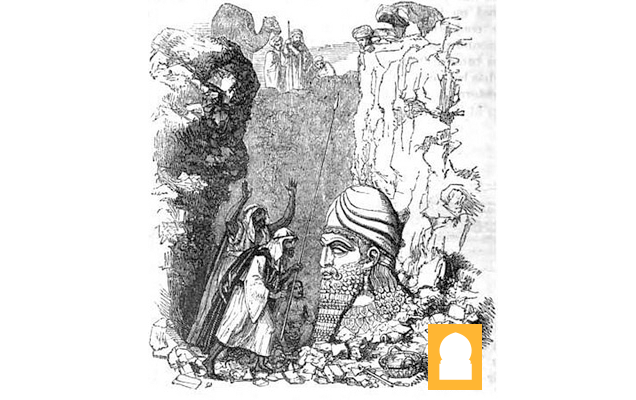

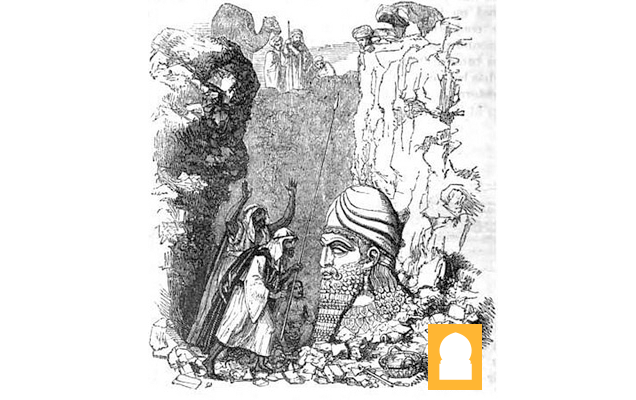

An interest in finding the locations of cities mentioned in the Bible (such as Nineveh and Babylon) inspired the original English and French nineteenth century archaeological expeditions to the Near East. These sites were discovered and their excavations revealed to the world a style of art which had been lost.

The excavations inspired The Nineveh Court at the 1851 World's Fair in London and a style of decorative art and architecture called Assyrian Revival. Ancient Near Eastern art remains popular today; in 2007 a 2.25 inch high, early 3rd millennium limestone sculpture, the Guennol Lioness, was sold for 57.2 million dollars, the second most expensive piece of sculpture sold at that time.

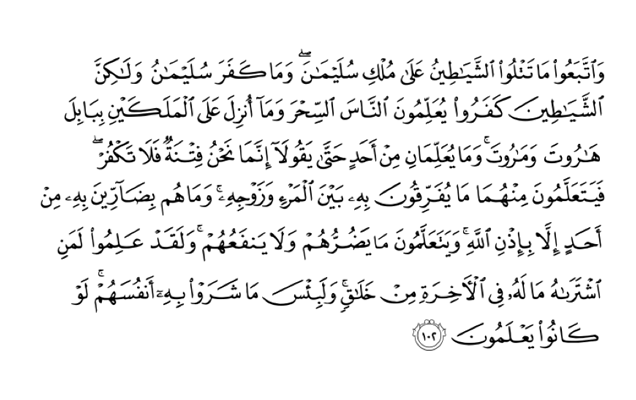

Also In the Qur'an

Babylon is referred to in verse (2:102) of chapter (2) sūrat l-baqarah (The Cow):

It was not Solomon who disbelieved, but the devils disbelieved, teaching people magic and that which was revealed to the two angels at Babylon, Harut and Marut.

A Complex History

The history of the Ancient Near East is complex and the names of rulers and locations are often difficult to read, pronounce and spell. Moreover, this is a part of the world which today remains remote from the West culturally while political tensions have impeded mutual understanding. However, once you get a handle on the general geography of the area and its history, the art reveals itself as uniquely beautiful, intimate and fascinating in its complexity.

Geography and the Growth of Cities

Mesopotamia remains a region of stark geographical contrasts: vast deserts rimmed by rugged mountain ranges, punctuated by lush oases. Flowing through this topography are rivers and it was the irrigation systems that drew off the water from these rivers, specifically in southern Mesopotamia, that provided the support for the very early urban centers here.

The region lacks stone (for building) and precious metals and timber. Historically, it has relied on the long-distance trade of its agricultural products to secure these materials. The large-scale irrigation systems and labor required for extensive farming was managed by a centralized authority. The early development of this authority, over large numbers of people in an urban center, is really what distinguishes Mesopotamia and gives it a special position in the history of Western culture. Here, for the first time, thanks to ample food and a strong administrative class, the West develops a very high level of craft specialization and artistic production.

Text by Dr. Senta German

Babylonian Art

Hammurabi: The king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient

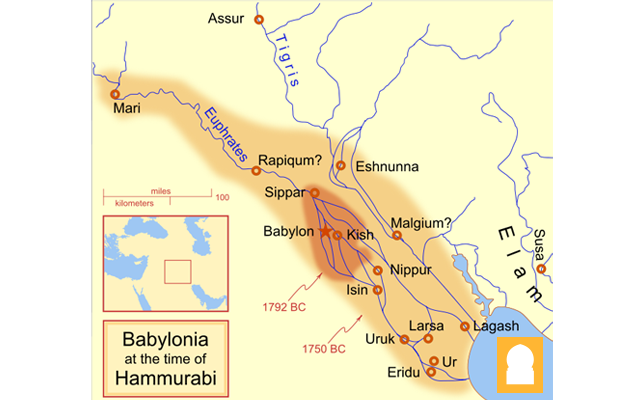

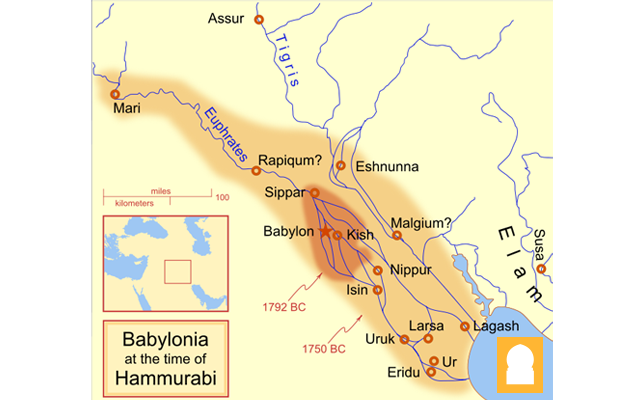

The second millennium’s beginning is characterized by the rise of two warring city states, Isin and Larsa, a competition which Isin loses, conquered by Rim-Sin 1822-1763 B.C.E.

After thirty years of attempted consolidation, Rim-Sin was ousted by Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.E.) of the city state of Babylon.

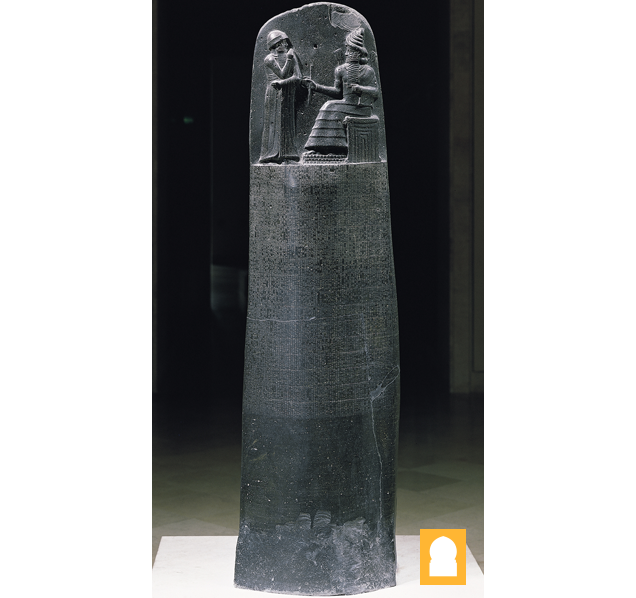

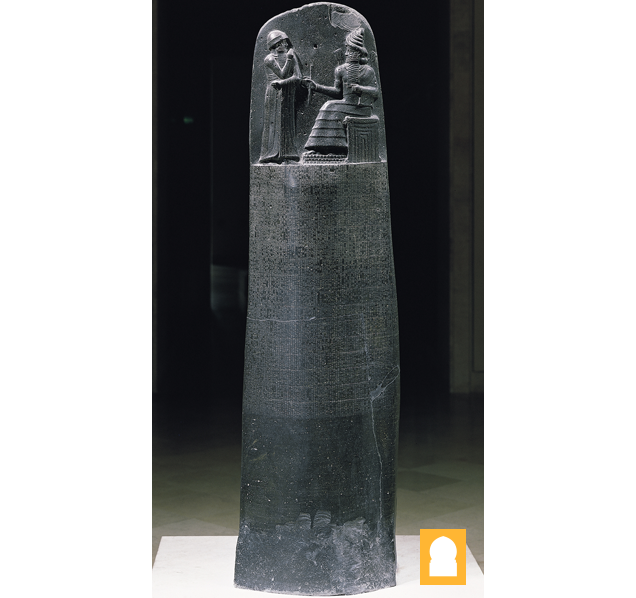

Over the next few years, Hammurabi conquered much of northern and western Mesopotamia and by 1776 B.C.E., he is the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Documents show Hammurabi was a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule, and this is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets (a stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving). We can also view this as a monument presenting Hammurabi as an exemplary king of justice.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god.

Unfinished Kudurru

During the 2nd millennium, the northern (Assyria) and southern (Babylonia) regions of Mesopotamia (together with Egypt and the Hittite lands, in what is now modern Turkey) grew strong and exercised surprisingly harmonious political relations. For art, this meant an easy exchange of ideas and techniques, and surviving texts reflect the development of “guilds” of craftsmen, such as jewelers, scribes and architects.

"Unfinished" Kudurru, Kassite period, attributed to the reign of Melishipak, 1186–1172 B.C.E., found in Susa, where it had been taken as war booty in the 12th century B.C.E.

Babylonia at this time was held by the Kassites, originally from the Zagros mountains to the north, who sought to imitate Mesopotamian styles of art. Kudurru (boundary markers) are the only significant remains of the Kassites, many of which show Kassite gods and activities translated into the visual style of Mesopotamia.

This Kudurru, unfinished as it lacks its inscription, would have marked the boundary of a plot of land, and likely would have listed the owner and even the person to whom it was leased.

Although an object made and intended for Kassite use, it bears Babylonian style and imagery, especially the multiple strips or registers of characters and the stately procession of gods and lions.

The Kassites eventually succumb in the general collapse of Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C.E. This is a period charaterized by famine, widespread political instability, roving mercenaries and, very likely, plague. This regional collapse affected states as far away as mainland Greece and as great as Egypt. It is often referred to as the first Dark Ages.

Text by Dr. Senta German

Although an object made and intended for Kassite use, it bears Babylonian style and imagery, especially the multiple strips or registers of characters and the stately procession of gods and lions.

The Kassites eventually succumb in the general collapse of Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C.E. This is a period charaterized by famine, widespread political instability, roving mercenaries and, very likely, plague. This regional collapse affected states as far away as mainland Greece and as great as Egypt. It is often referred to as the first Dark Ages.

Text by Dr. Senta German

Assyrian Art

A Military Culture

The Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East for the first half of the first millennium, led by a series of highly ambitious and aggressive warrior kings. Assyrian society was entirely military, with men obliged to fight in the army at any time. State offices were also under the purview of the military.

Indeed, the culture of the Assyrians was brutal, the army seldom marching on the battlefield but rather terrorizing opponents into submission who, once conquered, were tortured, raped, beheaded, and flayed with their corpses publicly displayed. The Assyrians torched enemies' houses, salted their fields, and cut down their orchards.

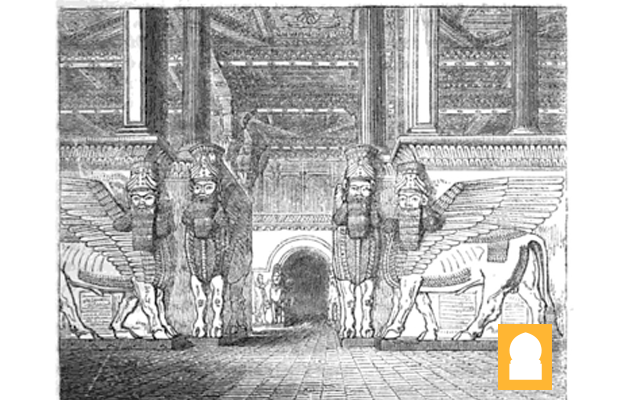

Luxurious Palaces

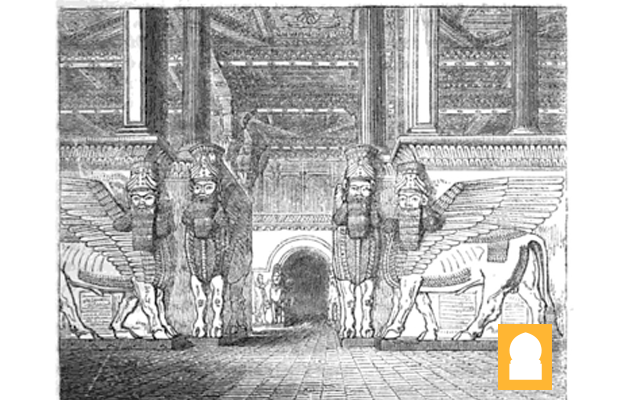

As a result of these fierce and successful military campaigns, the Assyrians acquired massive resources from all over the Near East which made the Assyrian kings very rich. Some of this wealth was spent on the construction of several gigantic and luxurious palaces spread throughout the region.

The palaces were on an entirely new scale of size and glamor; one contemporary text describes the inauguration of the palace of Kalhu, built by Assurnasirpal II (who reigned in the early 9th century), to which almost 70,000 people were invited to banquet. The interior public reception rooms of Assyrian palaces were lined with large scale carved limestone reliefs which offer beautiful and terrifying images of the power and wealth of the Assyrian kings and some of the most beautiful and captivating images in all of ancient Near Eastern art.

Feats of Bravery

Like all Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal decorated the public walls of his palace with images of himself performing great feats of bravery, strength and skill. Among these he included a lion hunt in which we see him coolly taking aim at a lion in front of his charging chariot, while his assistants fend off another lion attacking at the rear.

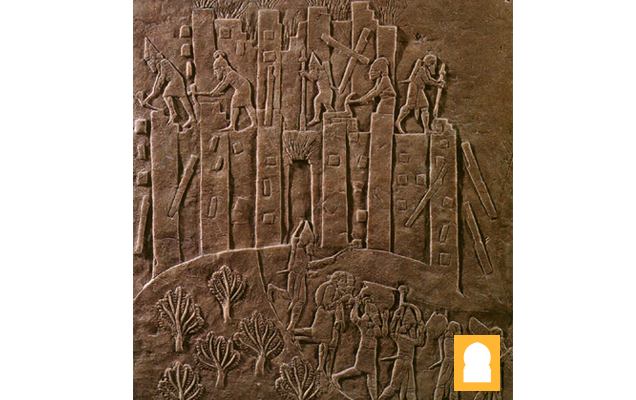

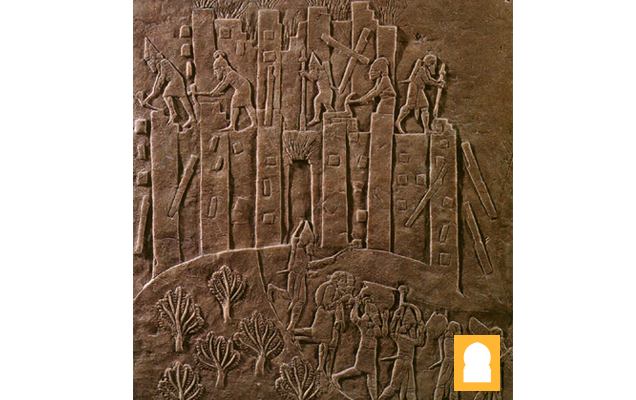

The Destruction of Susa

One of the accomplishments Ashurbanipal was most proud of was the total destruction of the city of Susa. In this relief, we see Ashurbanipal’s troops destroying the walls of Susa with picks and hammers while fire rages within the walls of the city.

Military Victories & Exploits

In the Central Palace at Nimrud, the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III illustrates his military victories and exploits, including the siege of a city in great detail. In this scene we see one soldier holding a large screen to protect two archers who are taking aim. The topography includes three different trees and a roaring river, most likely setting the scene in and around the Tigris or Euphrates rivers.

Text by Dr. Senta German

Neo-Babylonian Art

The Assyrian Empire Ends

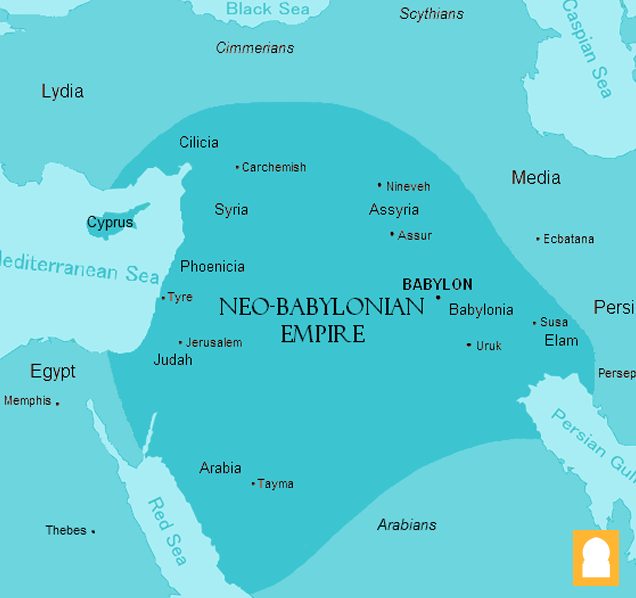

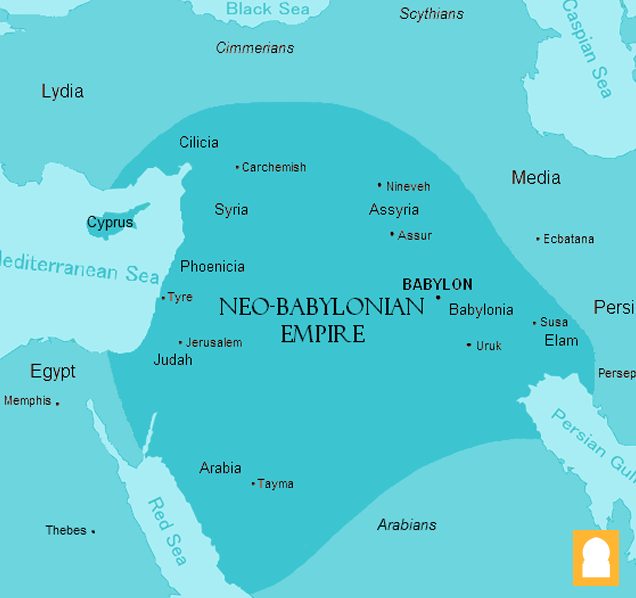

The Assyrian Empire which had previously dominated the Near East came to an end at around 600 B.C.E. due to a number of factors including military pressure by the Medes (a pastoral mountain people, again from the Zagros mountain range), the Babylonians, and possibly also civil war.

A Neo-Babylonian Dynasty

The Babylonians rose to power in the late 7th century and were heirs of the urban traditions which had long existed in southern Mesopotamia. They eventually ruled an empire as dominant in the Near East as that held by the Assyrians before them.

This period is called Neo-Babylonian (or new Babylonia) because Babylon had also risen to power earlier and became an independent city-state, most famously during the reign of King Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.E.).

In the art of the Neo-Babylonian Empire we see an effort to invoke the styles and iconography of the 3rd millennium rulers of Babylonia. In fact, one Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, found a statue of Sargon of Akkad, set it in a temple and provided it with regular offerings.

Architecture

The Neo-Babylonians are most famous for their architecture, notably at their capital city, Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar (604-561 B.C.E.) largely rebuilt this ancient city including its walls and seven gates. It is also during this era that Nebuchadnezzar purportedly built the "Hanging Gardens of Babylon" for his wife because she missed the gardens of her homeland in Media (modern day Iran). Though mentioned by ancient Greek and Roman writers, the "Hanging Gardens" may, in fact, be legendary.

The Ishtar Gate

The Ishtar Gate (today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin) was the most elaborate of the inner city gates constructed in Babylon in antiquity. The whole gate was covered in lapis lazuli glazed bricks which would have rendered the façade with a jewel-like shine. Alternating rows of lion and cattle march in a relief procession across the gleaming blue surface of the gate.

Text by Dr. Senta German

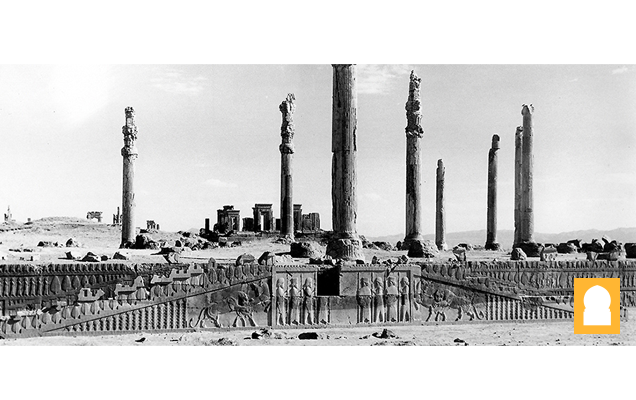

Art of the Persian Empire

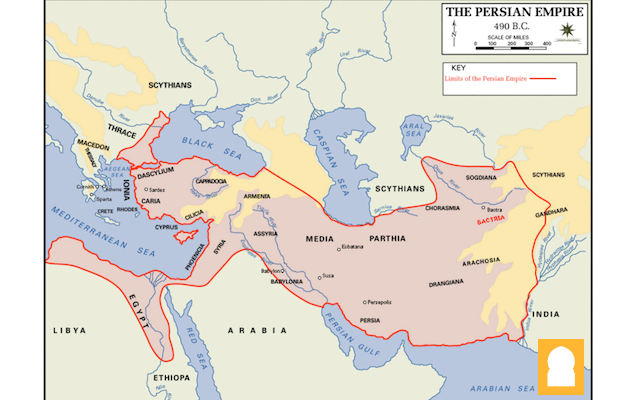

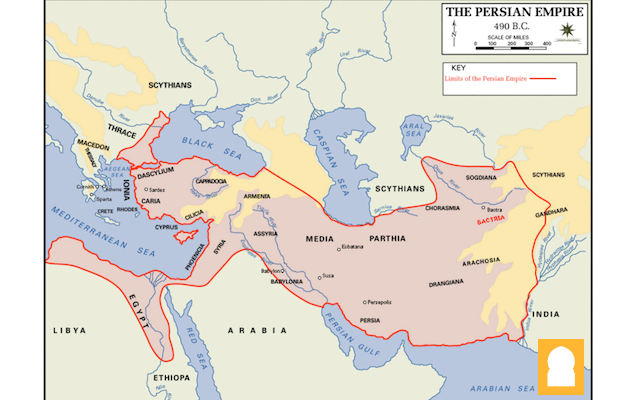

The heart of ancient Persia is in what is now southwest Iran, in the region called the Fars. In the second half of the 6th century, the Persians (also called the Achaemenids) created an enormous empire reaching from the Indus Valley to Northern Greece and from Central Asia to Egypt.

Although the surviving literary sources on the Persian empire were written by ancient Greeks who were the sworn enemies of the Persians and highly contemptuous of them, the Persians were in fact quite tolerant and ruled a multi-ethnic empire. Persia was the first empire known to have acknowledged the different faiths, languages and political organizations of its subjects.

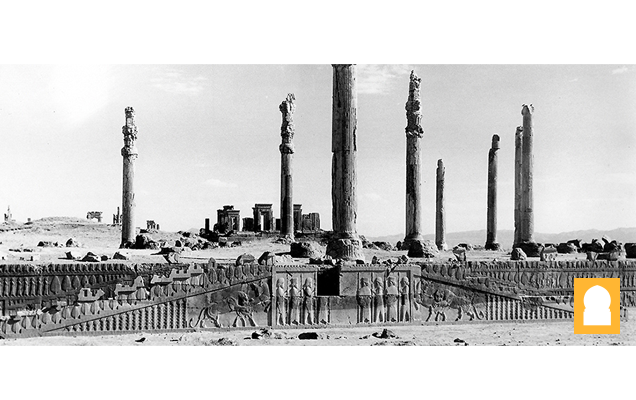

This tolerance for the cultures under Persian control carried over into administration. In the lands which they conquered, the Persians continued to use indigenous languages and administrative structures. For example, The Persians accepted hieroglyphic script written on papyrus in Egypt and traditional Babylonian record keeping in cuneiform in Mesopotamia. The Persians must have been very proud of this new approach to empire as can be seen in the representation of the many different peoples in the reliefs from Persepolis, a city founded by Darius the Great in the 6th century B.C.E.

Persepolis included a massive columned hall used for receptions by the Kings, called the Apadana. This hall contained 72 columns and two monumental stairways. The walls of the spaces and stairs leading up to the reception hall were carved with hundreds of figures, several of which illustrated subject peoples of various ethnicities, bringing tribute to the Persian king.

The Persian Empire was, famously, conquered by Alexander the Great. Alexander no doubt was impressed by the Persian system of absorbing and retaining local language and traditions as he imitated this system himself in the vast lands he won in battle. Indeed, Alexander made a point of burying the last Persian emperor, Darius III, in a lavish and respectful way in the royal tombs near Persepolis. This enabled Alexander to claim title to the Persian throne and legitimize his control over the greatest empire of the Ancient Near East.

Text by Dr. Senta German

Although an object made and intended for Kassite use, it bears Babylonian style and imagery, especially the multiple strips or registers of characters and the stately procession of gods and lions.

The Kassites eventually succumb in the general collapse of Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C.E. This is a period charaterized by famine, widespread political instability, roving mercenaries and, very likely, plague. This regional collapse affected states as far away as mainland Greece and as great as Egypt. It is often referred to as the first Dark Ages.

Text by Dr. Senta German

Although an object made and intended for Kassite use, it bears Babylonian style and imagery, especially the multiple strips or registers of characters and the stately procession of gods and lions.

The Kassites eventually succumb in the general collapse of Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C.E. This is a period charaterized by famine, widespread political instability, roving mercenaries and, very likely, plague. This regional collapse affected states as far away as mainland Greece and as great as Egypt. It is often referred to as the first Dark Ages.

Text by Dr. Senta German